By Seth Brown

Some hunts are about meat. Some are about antlers, or manes. And some—like this one—are about validation. Not of self, but of gear. In particular, a rifle.

After a week of grinding through five gym sessions and long hours at work, I loaded up the truck on a brisk Saturday morning and pointed it toward the backcountry. I had one mission: to test and validate my long-range hunting setup. The rifle—a custom-built Remington 700 chambered in .338 Edge—was loaded with 300 grain Berger VLDs, moving at 2650fps. She’s topped with a Nightforce ATACR 4-16×50 in Talley rings, and breaks crisply on a Timney trigger. This was the first real hunt I’d use it on, and it was time to see if it performed as well in the field as it did on paper.

The Approach

I borrowed a 4WD to cover the initial stretch of riverbed, parking at the base of a mountain stream. From there, I shouldered my pack and started up the valley on foot. The plan was to camp overnight, so I’d brought my Mont Moondance FN 2P tent. I’d never pitched it before, but it proved excellent—quick to set up, perfectly pre-guyed, and warm enough to handle sub-zero alpine temperatures with ease. It reminded me of the MSR Hubba Hubba, but with more attention to the details.

I glassed the slopes as I climbed, noticing something odd: most of the tahr were on the shaded, western side of the valley. This ran counter to my experiences with deer and chamois, which tend to favour the warmer flanks in winter. Still, the signs were there, and by early afternoon I’d spotted a group of mature bulls bedded high, around 1100m elevation—about 300 vertical metres above the streambed.

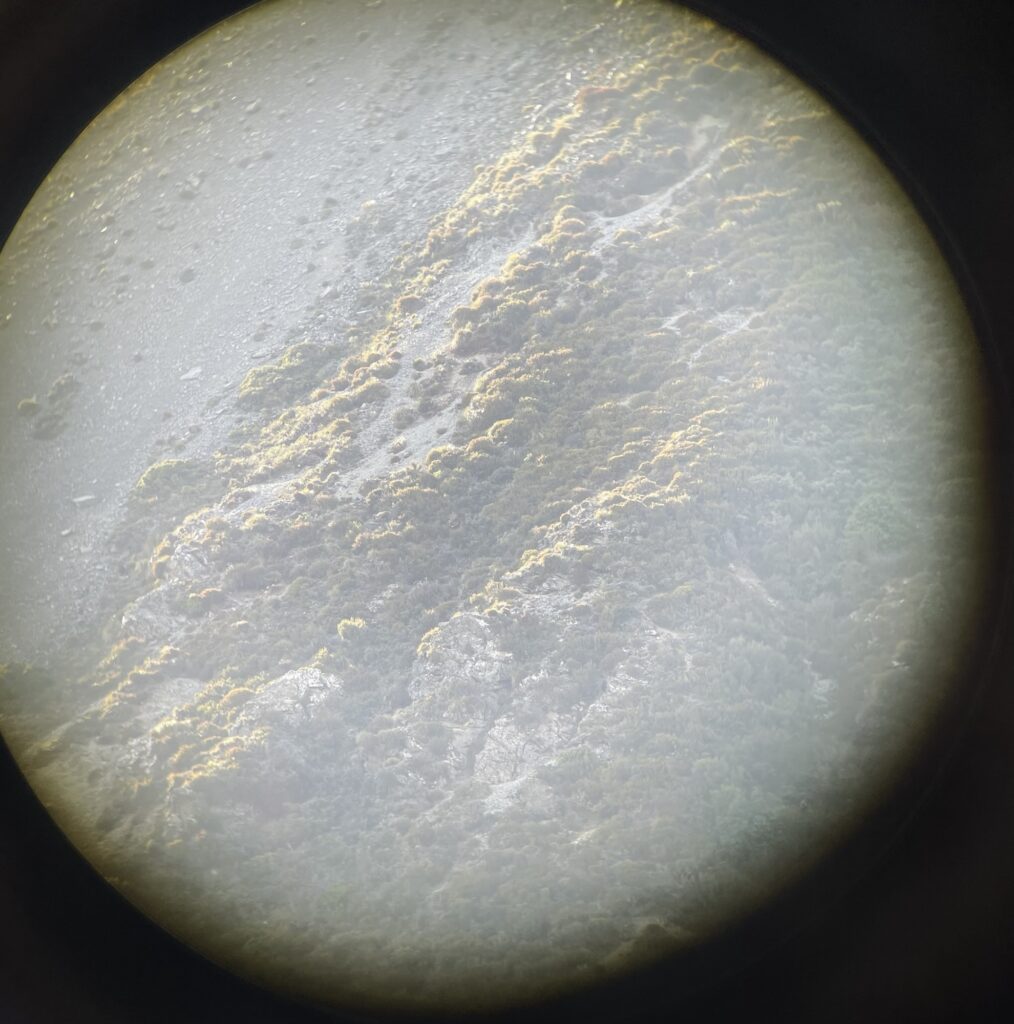

Image right with tahr in the shade in the scrub, taken through my binoculars (should have carried the spotting scope)

First Shots

The sun was blazing and the angle steep, but I found a shooting position with limited concealment. The bulls clearly saw me but didn’t spook—typical behaviour for tahr at range. They just held their position.

I wasn’t confident at 500m, having only recently zeroed the rifle and recorded its velocity. My Kestrel hadn’t been MV-calibrated, but I trusted my reloads and the chronograph numbers.

Luckily, a younger bull presented at 320m—much more manageable. I dialled 1.5 mils for elevation and settled in. The position was steep and awkward, seated behind a bipod with a small rear bag on a rock. The rifle barked and the shot landed. The bull tumbled through the scrub—textbook terminal performance from the 300 grain VLD.

I turned my attention back to the larger bulls. One presented at 527m. I dialled 3.3 mils. The rifle bucked hard on the lightweight Spartan bipod, but I managed to spot my shot through the scope. The bull stumbled, moved uphill briefly, then faltered again. I chambered a follow-up from my bino harness and fired. This time he dropped out of sight, collapsing behind a lip in the terrain.

The Climb

I packed the rifle, loaded my gear, and began the steep climb. I’ve learned over the years to manage these grinds mentally—focusing on short milestones. “Just to that tussock… just to that rock… then rest.” My boots were worn, the tread rounded from many kilometres, but they held together.

First, I found the younger bull—dead in the tussock with a solid blood trail. I marked the position. I considered turning back, but I’ve learned not to trust that voice offering the easy way out. I pressed upward toward the larger bull.

After cresting an outcrop and navigating deceptive ground, I finally spotted him. His thick winter mane was draped over the clay. A magnificent bull, though not rug-worthy—both shots had passed clean through, one leaving an exit wound almost three inches across.

Definitely not the largest bull I’ve ever shot, but definitely the furthest shot I’ve taken on a large game animal.

The Recovery

I butchered the bull, taking the hind legs, back steaks, and head. My hips and knees are too old to carry more than I must. As I worked, a kea landed nearby, showing the usual cheeky curiosity. He pecked at my meat bag until I threw scraps at him to keep him occupied—better than throwing stones. I’ve always appreciated keas; they’re survivors like the rest of us.

Then I returned to the smaller bull, gave him the same treatment, and left his head behind. I did regret shooting him—but the freezer needs meat.

Reflection

Crossing the stream and hiking back to camp, I had time to think. Sometimes I forget the scale of these missions. I almost regard them as routine, but for many they’re not. The rifle performed well. The loads were consistent. The tent kept me warm. The terrain was harsh but familiar.

More than anything, I felt satisfied. This wasn’t just a hunt. It was a test of systems, mindset, and preparation. Validation not just of a tool, but of a lifestyle.

Resilient Hunter NZ is built on the belief that experience, consistency, and mental toughness make the difference in the backcountry. Follow for gear reviews, training principles, and honest accounts from New Zealand’s high country.