By Seth Brown – Resilient Hunter NZ

Reloading attracts more mythology than almost any other part of shooting.

Spend ten minutes on any forum and you’ll find people insisting that you must neck-turn, batch weigh brass, mic neck tension, seat to the lands, or buy a boutique press to build “good ammo.”

But after years of loading everything from standard hunting cartridges through to large magnums like .375 CheyTac — plus all the mistakes I made along the way — the lesson has become simple:

You can only meaningfully control the variables you can accurately measure.

And you don’t need premium equipment to produce perfectly acceptable hunting ammunition.

You can make excellent, reliable ammo with modest tools — but you must be honest about which variables can actually be measured and controlled.

Measurement Beats Equipment

Reloaders often chase invisible variables they cannot quantify.

This mindset appears everywhere — in online discussions, in clubrooms, and in the language of “precision reloading.”

The reality is much more straightforward:

- You do not need a $2,000 press.

- You do not need micron-accurate mandrels.

- You do not need to weigh every projectile.

- You do not need perfect symmetry in your brass.

What matters is control, and control only exists where measurement does.

My Reloading Setup (And Why It Isn’t Exotic)

My bench is built for practicality and workflow, not prestige.

Lyman Brass Smith — Entry-Level, Entirely Adequate

A simple G-frame press permanently fitted with a Lee Universal Decapping Die.

This handles all depriming and doesn’t need to do anything more.

Redding Boss Press — The Workhorse

Used for resizing and seating of standard long- and short-action cartridges.

Rigid, smooth, predictable.

RCBS Rock Chucker Supreme — For Large Cartridges

Reserved for extremely large or unconventional magnums like .375 CheyTac.

Massive leverage and very consistent.

None of these presses are boutique or “precision” instruments.

They don’t need to be.

Presses move brass.

They do not measure anything.

Powder Charge: The One Variable That Truly Matters

I use an AutoTrickler V2 feeding an A&D FX-300i laboratory scale.

The critical component is the scale, offering 0.02-grain resolution with stable calibration.

This directly affects the most important ballistic variable you can meaningfully control:

Muzzle Velocity Consistency (SD/ES)

SD and ES translate directly into vertical dispersion at distance.

For field shooting, this matters far more than seating tricks or component voodoo.

Earlier Tools and Why I Moved On

Before upgrading, I ran two Lyman Gen 6 dispensers.

They worked, but I never fully trusted their stated accuracy — and they were slow enough that I needed two to maintain workflow.

A fast trickler and lab-grade scale fixed both problems.

Cartridge Measurements: CBTO and Why It Matters

I use Mitutoyo digital calipers to measure Cartridge Base-to-Ogive (CBTO) because the ogive is the only truly repeatable bearing surface.

Bullet tips are not:

- plastic tips deform

- bonded tips broom

- fine match points like Berger VLD are fragile

Measuring COAL to thousandths of an inch is an illusion; the tip isn’t a stable reference.

CBTO is measurable.

COAL often isn’t.

This is the core theme:

measure only what you can measure properly.

Neck Tension: The Variable Most People Pretend to Control

I do not chase neck tension with mandrels or bushings.

Why?

Because I don’t have the tools needed to measure real neck tension variation at the required resolution — and most reloaders don’t either.

Trying to “control” a variable you cannot measure is just guesswork.

What I Do Control: Annealing

I anneal every firing using an AMP annealer.

This has dramatically increased brass life and reduced neck variability.

Anecdote: The Cost of Not Annealing

Early in my 6.5 Creedmoor days, I loaded Norma brass without annealing.

By the 7th or 8th firing, I was seeing neck splits and binned the entire set.

Annealing fixed a real, measurable problem — not a theoretical one.

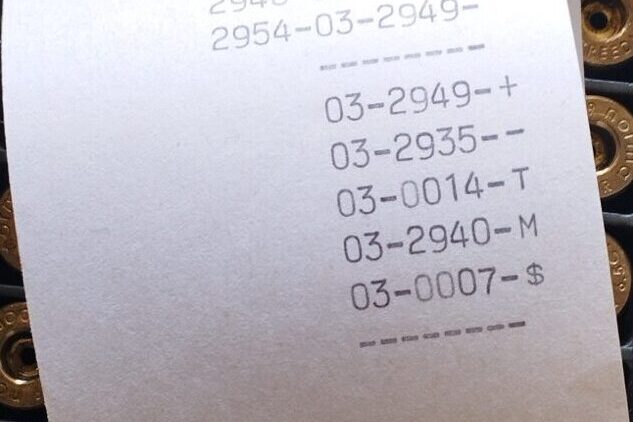

Brass Management: One of the Few Useful Systems

I manage brass in sets of 30 or more pieces.

This allows me to:

- track firing count

- track annealing cycles

- track processing stage

- manage attrition (tussock eats brass)

This keeps lifecycle variation low and predictable.

The Myth of “Chasing the Lands”: Why I Stopped Doing It

A common belief is that seating depth must be set “10 thou off the lands.”

In reality, this approach is flawed for hunting rifles.

Lands Move as the Barrel Wears

Lands erode from the first shot.

Your “10 thou off” load becomes “40 thou off” after a few hundred rounds.

This is not a stable tuning point.

Magazine Length Is the Real Limiting Factor

Most rifles impose a mechanical constraint:

internal magazine length.

Example: A Tikka T3/T3x long-action magazine is roughly 3.34” (84.8 mm) internally.

Many long, high-BC bullets cannot be seated near the lands without exceeding this limit.

This leads shooters to:

- seat long

- exceed magazine capacity

- single-feed their rounds

…believing they are chasing accuracy.

I Fell For This Too

When loading for my .338 Edge (338-300 RUM), I initially single-fed for this exact reason.

With experience, I realised the truth:

- the perceived precision gain was marginal

- losing magazine functionality was a major tactical disadvantage

- for hunting, this was nonsense

Reliability Beats Imagined Precision

For NZ hunting, the correct priorities are:

- reliable feeding from the magazine

- safe, predictable pressures

- repeatable seating within magazine constraints

- consistent muzzle velocity

A theoretical 0.25-MOA gain means nothing if your rifle becomes a single-shot.

Shooter Reality: Practical Accuracy Is Worse Than People Admit

Most competent shooters produce around 4 MOA in real field conditions.

Not because they’re poor shots — but because field shooting is unstable:

- awkward positions

- uneven terrain

- wind

- movement

- heart rate

- imperfect rests

- time pressure

Meanwhile, internet discussions obsess over the distinction between a 0.5 and 1.5 MOA rifle.

Weapon Employment Zone modelling shows that difference equates to only about 10–15% hit probability at 400–500 m on a 5″ target.

Important? Yes.

Field-relevant? Rarely.

Chronographs: Measuring MV Properly

The only way to know your true muzzle velocity is to measure it, and the reliability of that measurement depends entirely on the chronograph you use and how well you set it up.

I’ve used many systems over the years. They are not equal.

Oehler 35P — The Old King

For decades, the Oehler 35P was considered the gold standard.

When set up correctly, it produces extremely reliable data — but “correctly” includes:

- precise sky-screen spacing

- exact alignment

- stable lighting

- placement 10–15 ft ahead of the muzzle

- additional care if using muzzle brakes (blast can trigger sensors)

The Oehler works beautifully, but setup is slow and space-demanding.

LabRadar — Excellent in Theory, Fussy in Practice

The concept is excellent.

The execution is temperamental.

It is sensitive to:

- exact alignment

- muzzle device type

- recoil signature

- reflective surfaces

- minor angular errors

Great when it works. Frustrating when it doesn’t.

Garmin Xero C1 Pro — A Genuine Leap Forward

This is the chronograph that changed everything for me.

It offers:

- near-instant setup

- no downrange equipment

- no alignment sensitivity

- consistency across muzzle devices

- pocket-sized portability

- reliable, repeatable readings

Why Chronograph Choice Matters

Without a chronograph, you are guessing.

With the wrong chronograph, you may be guessing with confidence — which is worse.

A reliable chronograph gives you:

- real MV

- SD and ES you can trust

- pressure detection

- trajectory verification

- barrel wear tracking

It doesn’t make your shooting more accurate — it makes your data accurate.

And accurate data is the foundation of all meaningful reloading decisions.

Measured vs “Calibrated” MV: Quantifying the Difference

Chronographs provide a measured MV.

Ballistic solvers (like the Kestrel 5700) allow you to “calibrate” MV based on observed impacts at distance.

This sounds important — but at typical NZ hunting ranges, the difference is surprisingly small.

Example: A Large MV Error

Take a typical 6.5 mm-class load at 870 m/s.

Now assume your chronograph is very wrong:

- true MV: 840 m/s

- solver MV: 870 m/s

- error: 30 m/s (~100 fps)

Approximate effect on drop:

- 300 m: ~4 cm

- 400 m: ~7–8 cm

- 500 m: ~10–12 cm

Compare this with field accuracy:

- a realistic 4 MOA field group at 400 m is about 45–50 cm

Even with a massive 100 fps error, your vertical shift is a small fraction of the shooter-induced dispersion.

When Does Calibrated MV Matter?

It becomes relevant when:

- you consistently shoot beyond 500–600 m

- from stable positions

- with genuinely sub-MOA systems

- in environments where you can trust wind calls

This is not how most NZ hunters operate.

At normal NZ hunting distances (300–400 m), a reasonable chronograph reading is more than good enough.

The extra work of MV calibration rarely provides meaningful benefit.

What Actually Matters for NZ Hunters

For almost all backcountry hunting situations:

- a rifle that can reliably shoot 1–1.5 MOA

- ammunition with reasonable SD/ES

- a shooter who can build a stable position

- a rifle that feeds from the magazine

- realistic wind and angle judgment

…will outperform any benchrest-inspired reloading technique.

Conclusion: Control Only What You Can Measure

Reloading becomes powerful when it is simple, measurable, and repeatable.

- If you can’t measure it, you can’t control it.

- If you can’t control it, it probably doesn’t matter.

- Reliable feeding beats theoretical precision.

- Consistent MV beats boutique hardware.

- Shooter skill beats all of it.

Precision isn’t magic — it’s just consistency applied to measurable variables.

For New Zealand hunters, that is more than enough.