By Seth Brown – Resilient Hunter NZ

I’d headed out for an overnight hunt not far from Christchurch. I climbed a high feature that overlooked a series of long, fingered ridges running north–south — each one covered in the usual South Island mix of matagouri, tussock, and monkey scrub.

As the light faded, I glassed across the ridges and counted four or five deer moving high up among the scrub-covered fingers. The closest one was at about 410 metres, but it appeared briefly in a gully and vanished again before I could even settle behind the rifle. Shooting light was gone not long after eight, and I made my way back to the tent.

The next morning brought more of the same. A hard north-westerly was pushing through — around 17 knots gusting 20 — and the deer were moving quickly, searching out pockets of feed on the leeward sides of the ridges, out of the wind. My vantage point faced directly into it, which was good for scent, but meant most of the animals were feeding just over the skyline from me.

It wasn’t until later in the morning that I finally had a chance. I’d shifted along one of the fingers and, looking below and to my right, saw a deer standing less than 150 metres away. She was looking at me, I was looking at her — the classic stand-off. The problem was that I could only see her by standing myself, peering over the top of a thick bush. I couldn’t drop prone, couldn’t build a stable rest, and by the time I tried to adjust she was gone.

That short moment left me thinking. I realised how narrow my idea of field ready shooting had become. It’s easy to lie prone on a flat range behind a bipod and rear bag, but that doesn’t always translate to a hillside full of matagouri and shifting wind. In the field, we don’t get to choose our position — the terrain does.

Refocusing on Practice

Coming home from that trip, I realised something else: I don’t shoot my hunting rifle enough.

In a professional context, I spend a significant amount of time maintaining and validating proficiency with firearms. We shoot regularly to sustain tactical competency, and the standard is clear — skill fades quickly if it’s not reinforced.

Yet the rifle I rely on to make ethical, high-consequence shots in the backcountry — my Forbes 6.5-284 Norma — probably sees fewer rounds in a year than I’d ever accept professionally. On reflection, that’s not good enough. The only time I seem to shoot it is at animals, and that’s not acceptable in terms of preparation or respect for the quarry.

So, I’ve set myself a new goal: to complete a structured, repeatable accuracy and positional test each month — one that measures practical skill, not just precision.

Another Hunt, Same Lesson

Not long after that first trip, I went out again — this time purely looking for venison. The weather across the southern Canterbury foothills was brutal: a north-westerly wind between 17 and 20 knots, gusting to 40 mph, and the classic mix of four seasons in one day. Blazing sun at midday gave way to sideways rain by afternoon, and by morning the tent was frozen solid.

I spent the later part of the afternoon hunting up a side stream above the main valley. Despite having seen a pair of chamois from camp earlier, I couldn’t locate any deer. As the light began to fade and the weather worsened, I decided to start back toward camp. My assessment was simple: the likelihood of finding animals in that weather was low.

Still, before turning around, I checked one last ridge. To my surprise, as I crested the top and looked up the stream, I spotted two spikers — young stags — roughly 660 metres away. Normally I wouldn’t shoot spikers, but after several hunts without meat for the freezer, pragmatism won.

The wind was savage and variable. My thoughts were simple:

- I can’t make a 660 m shot in this wind.

- They’re unlikely to walk closer.

- I have to close the distance myself.

I stalked up the stream, dragging through wet tussock and clambering over slick boulders, using the land’s folds for cover. The terrain was open and harsh — just tussock, matagouri, and spaniard grass on steep, eroded slopes.

I stopped at what I believed to be about 300 metres, ranging a feature behind my original vantage point. I stripped my rifle from the pack, removed the scope cover, and prepared to crest the next spur, expecting visual contact.

When I ranged again, I was just under 200 metres — much closer than expected. The spur sloped sharply left to right, offering no chance for a prone position. After my previous experience, I was ready for a kneeling or seated shot.

Cresting the last of the spur, I kept low. Initially I saw nothing — which is often the case when the angles change — until the two spikers materialised on a small flat below the ridge I’d first spotted them on. The wind was still hammering from behind. The deer spooked, moving down and toward me, briefly disappearing behind a fold.

I worked the bolt and applied the safety. They would either turn up-stream and away, or move closer into my lane. Moments later, they crossed the stream and climbed the steep opposite face — a hind in front, followed by a yearling, then the two spikers.

I took a seated position, turned the throw lever on the NXS down to 5×, knowing the hash marks would double at that magnification. At ranges between 180 and 240 metres, I’d be well within point-blank for deer-sized game.

I held on the shoulder of the hind. The shot didn’t feel perfect, but impact was immediate — she dropped into the scrub. The yearling moved away; I held high in the shoulder, fired, and missed. I cycled the bolt, fired again with a more central hold, and the yearling rolled. I chambered a spare round from my bino harness and took a sight on one of the now-confused spikers, estimating 250–280 metres. I held ¾ mil high; the shot went over with no visible effect — likely my own error. I fed in my last round and fired again. The spiker stumbled, tumbling into a rocky slip.

Reflection

That hunt reinforced what I’d already been thinking. It wasn’t the gear, or the ballistic chart, or the wind call that made the difference — it was positional shooting, decision-making, and practice. The work I’d done mentally after the earlier hunt was already starting to show in how I approached that shot sequence.

The goal now is simple: keep training with intent. Not just to confirm zero or test ammunition, but to practise the act of shooting in the same imperfect, uncomfortable positions we find in the mountains.

Practical Accuracy Testing

To put that into practice, I went to the range to complete a structured practical accuracy test designed to measure real-world shooting ability across multiple positions and time constraints.

The test involves twenty rounds fired over three serials, from a mix of field positions — prone, seated, kneeling, and standing — each with its own time and accuracy standard.

Serial 1 – Untimed:

Two rounds are fired from each position — prone, seated (unsupported), kneeling (unsupported), and standing (unsupported). There’s no time limit, and the focus is purely on stability and precision.

Serial 2 – Timed:

Two rounds are again fired from each position, but with a 20-second limit per position. This introduces the stress of time pressure and forces quick, repeatable setups.

Serial 3 – Transition:

One round is fired from each of the four positions in a single continuous 60-second string, either moving from standing down to prone or the reverse. This tests efficiency, transitions, and mental control under time.

Each position has an acceptable accuracy ring representing practical field standards:

- 7 MOA for standing

- 5 MOA for kneeling

- 3 MOA for seated

- 2 MOA for prone

The rifle starts with the magazine loaded, chamber empty, bolt forward and closed, held at port-arms — parallel to the ground and pointing downrange.

The optic is set to 2.5× magnification at the start, adjusted as needed before each string.

The sling is used for all positions except prone, which uses a bipod and rear bag.

For prone serials, the Spartan bipod is held in the left hand at the start and must be attached before taking position.

Results Summary

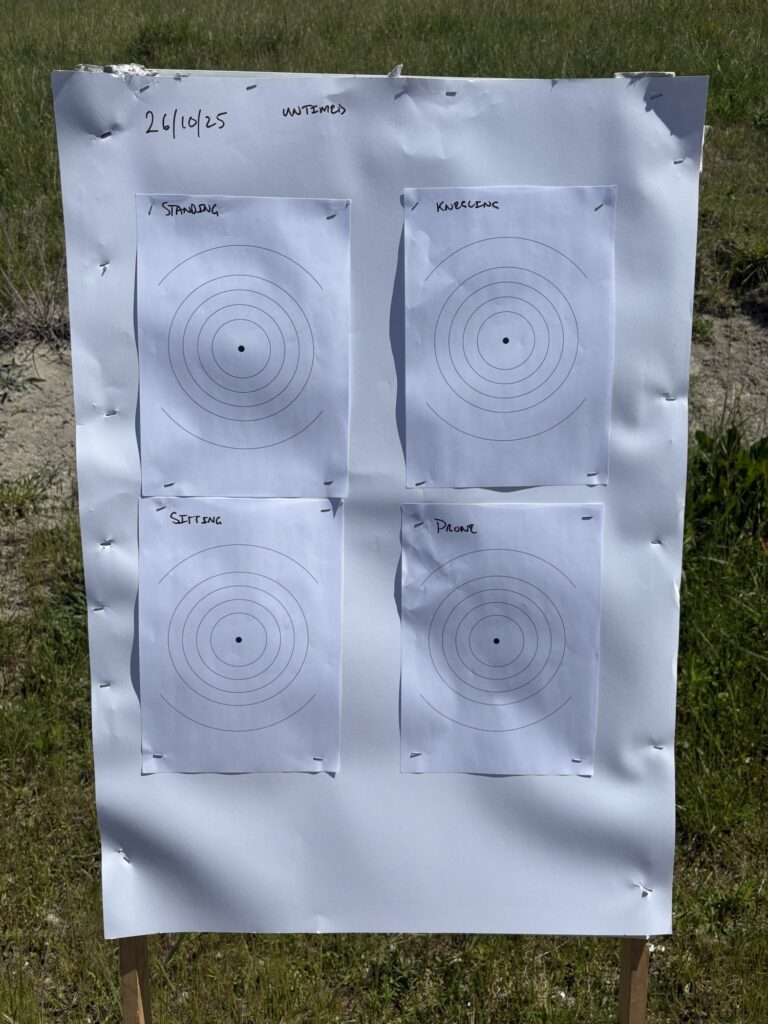

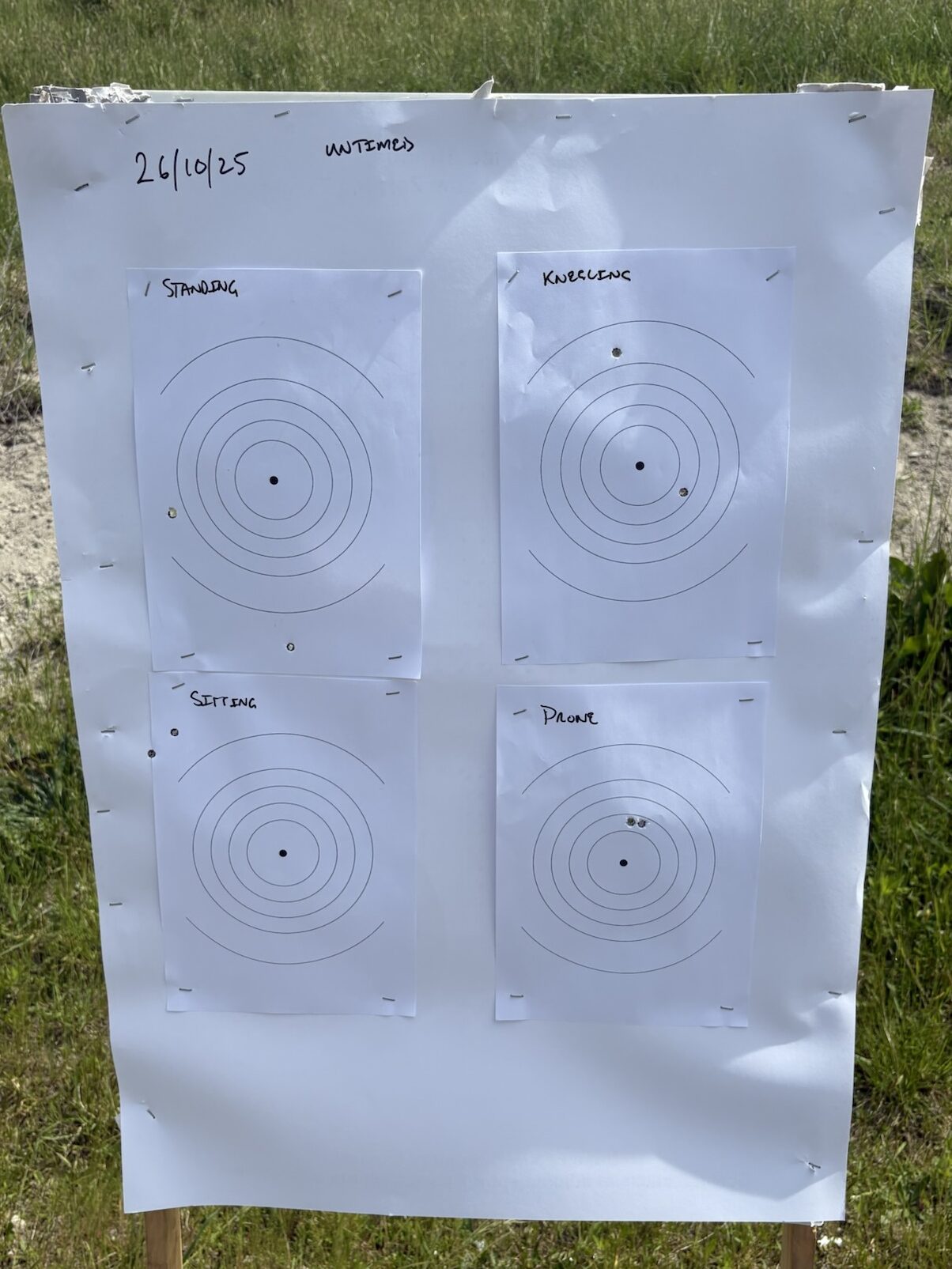

Un-timed Serial Results

This was the litmus test of sorts.

I did not go down range to check the target between shooting each of the positions. And this was a humbling experience when I finally did see the impacts.

As you can see from the image, almost none of the shots are within the acceptable accuracy rings for the respective positions.

I did learn that the rings themselves are too fine to distinguish at 100m through my 10 power Nightforce Scope, and in subsequent serials, as you’ll see, I darkened the respective lines with a permanent marker.

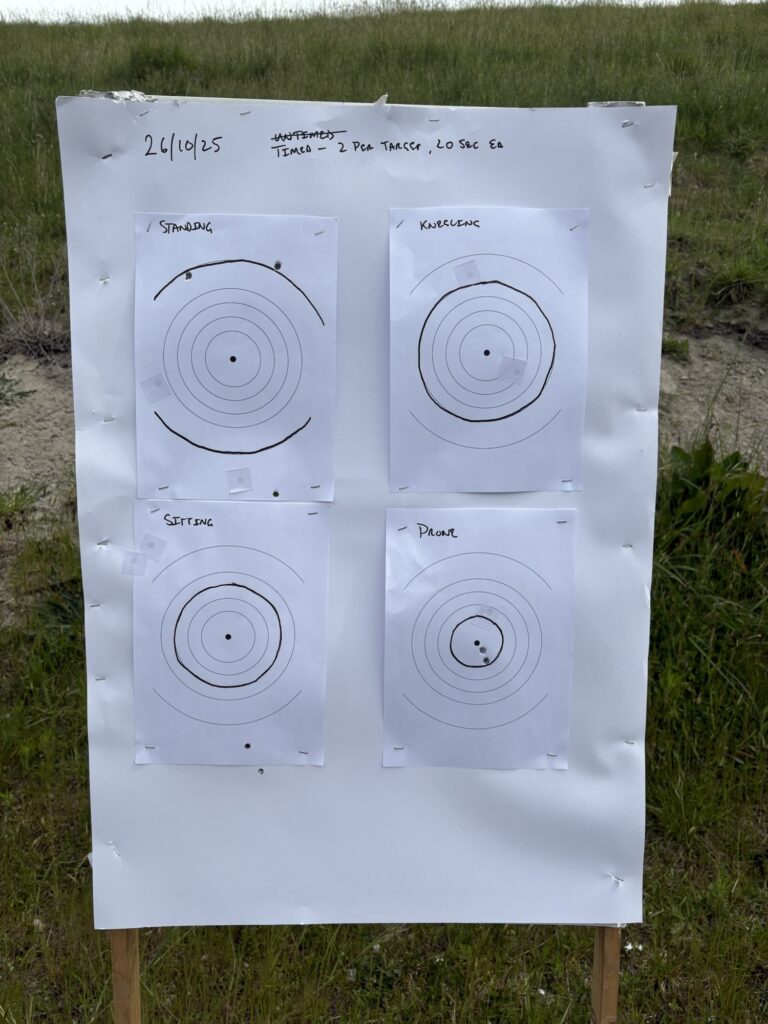

Timed Serial Results

The image to the right shows the results of the timed serials.

Somehow my accuracy improved on the standing and prone serials with the time pressure, rather than degrading. I can see some serious problems with my technique and setup from the kneeling unsupported position, as i managed to drop one of the rounds completely off of the target frame.

Times taken for each of the serials are shown below;

Standing: 2 impacts spread high and low across the target. Only one within the acceptable accuracy ring. (16.17 seconds).

Kneeling: One shot completely off of the target frame, (this is a common occurrence with my shooting obviously). The other shot as at the top right of the “standing” target. (18.23 seconds). Unstable despite sling tension.

Seated: Both shot (17.00 seconds).

Prone: 2 tight, well-centred impacts confirming zero (22.42 seconds — the only serial over time).

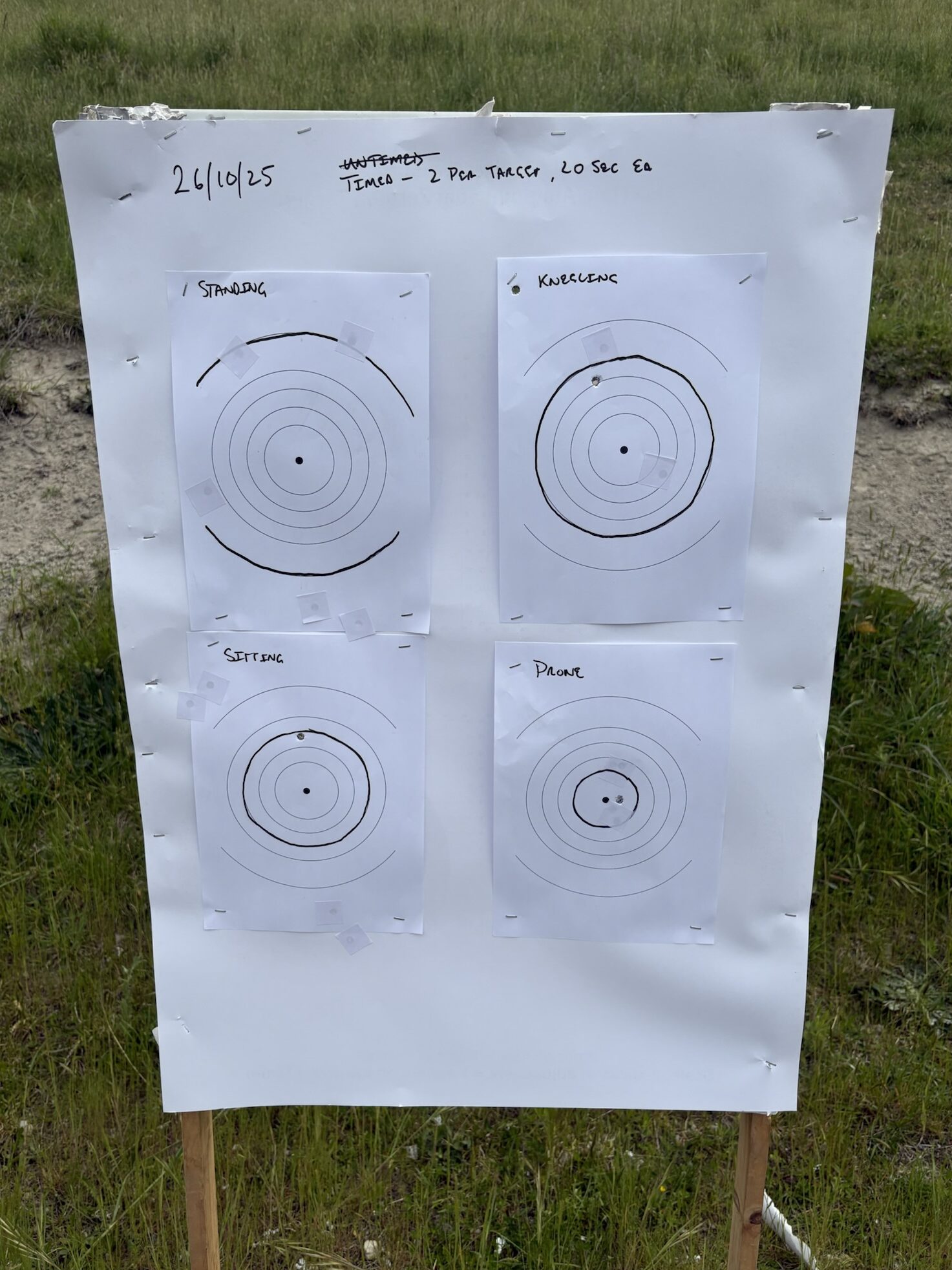

Transitional Serial (One Round Per Position)

Total time 58.84 seconds.

This serial or string represented a positive and a negative in terms of workflow.

The positive was that the magnification ring only needed to be adjusted once, at the beginning of the serial, and could be left there for the remainder of the rounds.

The negative was that the magazine of my rifle only holds three rounds, and generally I carry two additional rounds within the main compartment of my binocular harness. This entire serial required a reload. I chose to complete the reload before adopting the kneeling position, for both safety and ease of access to the spare ammunition.

The standing shot landed above the kneeling target; all others were within acceptable accuracy rings.

Conclusion

Looking back on the results, I was genuinely surprised.

For all my professional experience and perceived proficiency with firearms, the results were a reminder that familiarity isn’t the same as mastery. My positional stability, speed, and accuracy weren’t at the standard I’d expect of myself in a professional setting — and that was humbling.

It reinforced what I already believed: the number of rounds I’d fired through this rifle in recent years would be professionally unacceptable if judged by the standards I apply at work.

If I demand regular, structured practice in a tactical environment, why should I accept anything less from myself in the field, where the consequences of a poor shot are no less real?

This test didn’t just highlight the gaps — it confirmed that deliberate, consistent, accountable practice is the only way to close them.