By Seth Brown

Disclaimer: I am not a qualified physical trainer or physiotherapist. I am a middle-aged man with extensive backcountry experience, both recreational and professional. Over the years, I have subjected my body to physically demanding roles, including multiple rigorous assessment and selection processes. Despite this, I’ve remained largely injury-free. What follows is not medical or training advice, but a distillation of personal experience—what has worked for me in the bush, and what hasn’t.

“Enter the path here, and unsheathe your sword. There’s need of gall and resolution now.”

-The Aeneid, passage 360

There’s a certain truth about the New Zealand backcountry that doesn’t make it into social media posts or glossy magazine covers: it doesn’t care how fit you think you are. The hills don’t recognise rank, experience, or ego. They are indifferent to your plans. Out here, success is measured in hard yards, quiet suffering, and the ability to keep going when your legs are burning, your back is screaming, and you’ve still got a stag to carry out.

I’ve been hunting in Aotearoa since I was nineteen. My first real trip chasing red deer was in the Eastern Bay of Plenty, high above a winding river in late January. I shot three deer on the edge of a clearing just as the sun dipped behind the hills. With no real plan and even less experience, I decided to take them out whole—no boning, no quartering. The next four hours were a slow-motion disaster: one deer strapped to my back, the other two dragged and relayed over broken country in the stifling heat. It was agony. But it was also a lesson. That night etched into me what backcountry resilience really meant.

Since then, I’ve spent over a decade deliberately putting myself through hard things—physically and mentally. From demanding field-based military training and intense multi-day selection courses, to years of experience in tactical environments and law enforcement, I’ve come to understand resilience in a very practical way. And through all of it, I’ve found a deep overlap between the kind of grit needed to succeed in those environments and what’s required to be effective, safe, and successful in the mountains.

Understanding VO2 Max and Its Role in Endurance

Before diving into training methods, it’s important to understand one of the most vital performance indicators for backcountry hunting: VO2 max. VO2 max is the maximum rate at which your body can take in, transport, and use oxygen during exercise. It’s essentially a measure of your aerobic capacity.

High VO2 max levels are associated with better endurance, faster recovery, and greater work output over time. In the hills, where you’re often climbing with a pack, covering long distances, and working at moderate intensities for hours or days, a strong aerobic base is critical. It’s not about being the fastest or the strongest—it’s about who can keep going.

The higher your VO2 max, the more efficiently your body supplies oxygen to your muscles, delaying the onset of fatigue. For hunters, that means more time on your feet, more elevation gained, and less chance of making poor decisions due to exhaustion.

Train Like a Tactical Athlete

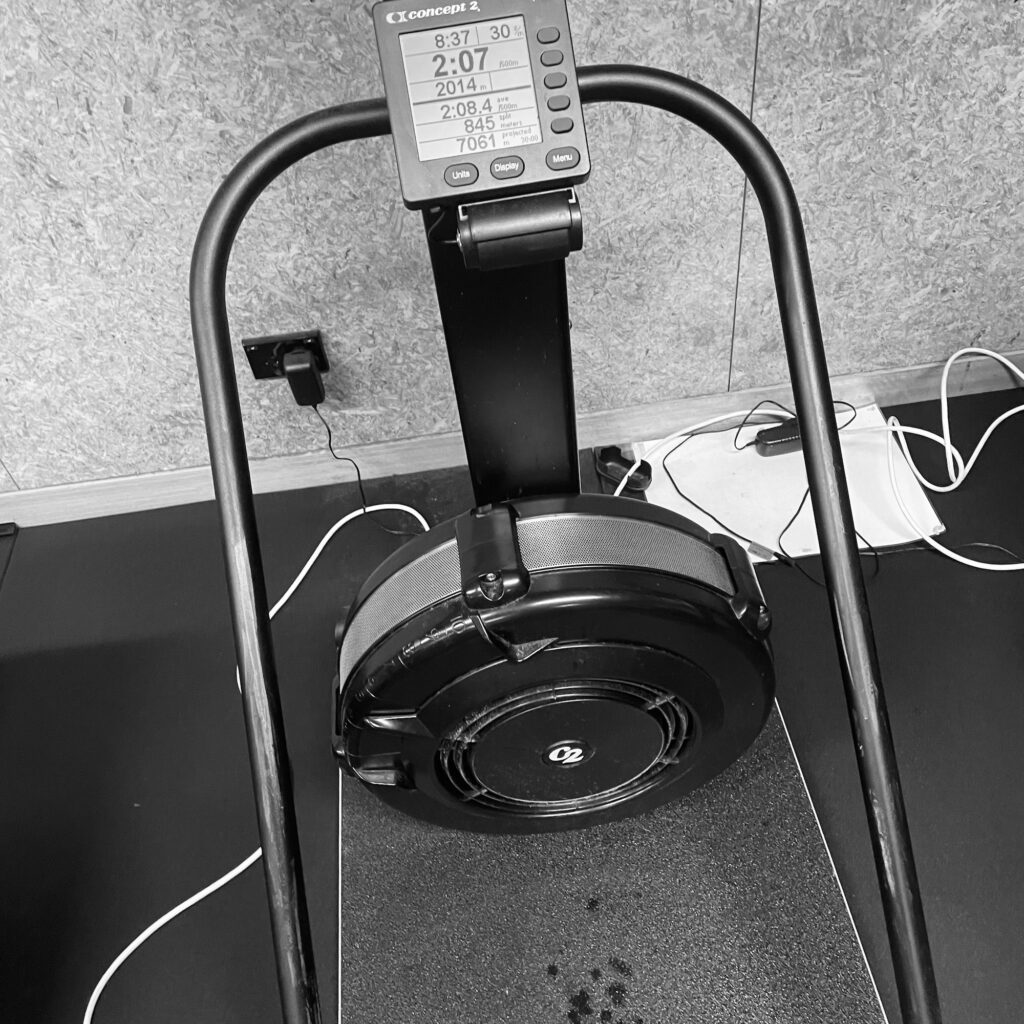

Over the past decade, I’ve followed what I call a “tactical athlete” model. It’s not about replicating the hunt. It’s about preparing the body to handle sustained stress, recover efficiently, and resist injury. That means mixed-modal training—rowing, biking, swimming, circuit-based strength and conditioning. The body doesn’t know if your lungs are working hard on a hill or on a rowing machine; it just knows there’s a demand for oxygen.

In 2020, at the peak of the Level 4 lockdown, I purchased an assault bike—an absolute beast of a machine. It seemed to me, and still seems to me, the silver bullet for inducing aerobic stress, without the potential for damage to ligaments. Stationary cycling is often used for rehabilitation following lower limb injuries such as ACL tears. So why not use a more intense, lower-impact machine for conditioning?

While on one of the qualification courses, we ran everywhere—every day—for months. I developed severe shin splints and lower limb pain that I carried with me through the early years of my career. Since then, I’ve avoided running as a primary training tool. These days, I mostly run for commuting, not conditioning.

Another early lesson from the tactical space was the introduction of pre-hab. We’re all familiar with rehab—the set of exercises assigned by a physio post-injury. Pre-hab is about getting ahead of the injury. It means strengthening common weak points before they fail: glutes, hips, knees, ankles, core. Backcountry hunters and tactical professionals face similar injury risks, and pre-hab is one of the best ways to keep moving forward.

Some of my favourite pre-hab movements include:

- Inverted overhead kettlebell press

- Cossack squats

- Weighted curtsie squats

- Banded single leg glute bridges

- Banded clams

Suggested Training Programs

- 3x weekly mixed-modal aerobic sessions (rower, ski-erg, bike, incline walking)

- 2x strength-focused days (compound lifts with accessory pre-hab movements)

- 1x skills day (navigation, glassing, rifle manipulation under fatigue)

- 1x recovery/mobility day

Consistency is the goal. You’re not training for aesthetics—you’re training for resilience, endurance, and mission success.

Recommended Pre-Hab for Lower Limbs

- Ankle stability drills – banded ankle rotations, single-leg balance work

- Glute activation – clamshells, lateral band walks, glute bridges

- Hip mobility – couch stretch, deep lunges, 90/90 rotations

- Core stability – dead bugs, bird-dogs, side planks

- Foot strength – barefoot walking, toe splaying, short foot drills

These movements can be done daily or cycled through in warm-ups. They reduce the risk of injury when carrying loads over uneven terrain.

My training approach focuses on two of the big three lifts—usually a variation of the squat (front squat) and a deadlift variation (trap bar or shovel bar). I don’t see bench press as essential; instead, I favour light power cleans or squat cleans for their functional utility.

For conditioning, I rely heavily on CrossFit-style METCON or interval-style workouts. Rarely do my aerobic sessions exceed an hour—they’re short, intense, and to the point. It’s about output per unit of time.

I also make good use of kettlebell work for core and stability. Key favourites include:

- Turkish get-ups

- Kettlebell windmills

- Kettlebell halos

I integrate skill work into my training sessions during “rest periods.” As a tactical athlete, this has traditionally meant dry fire practice under elevated heart rate. This simulates decision-making under duress, an incredibly useful training tool. For hunters, this could include:

- Wind reading drills with a Kestrel

- Map-to-ground navigation exercises

- Glassing drills

Be creative—practice the things you’ve failed at. Identify the tasks that go poorly when you’re fatigued, and train them into your system. The value isn’t just in the work—it’s in how you work under pressure.

The average length of my backcountry hunts over the past three years has been around 40km in three days. That’s no mean feat for a guy pushing middle age. I credit that to consistent training, aerobic development, and dedication to pre-hab routines.

Recovery Strategies

Recovery is where adaptation happens. It’s the invisible pillar of performance that determines whether you come back stronger—or not at all.

I incorporate regular sauna and cold plunge sessions into my weekly routine, especially following multi-day hunts. The combination of heat and cold exposure provides a number of physical and psychological benefits:

- Reduced inflammation: Alternating hot and cold helps flush waste products from the muscles and reduces swelling.

- Improved circulation: The rapid change in temperature helps improve vascular function and stimulates blood flow.

- Faster muscle recovery: I find that this reduces muscle soreness and increases my bounce-back from hard efforts.

- Mental reset: The discomfort of cold water offers mental resilience benefits—it helps me to stay calm and present under stress.

Even once a week, this practice has helped me rebound more effectively after big efforts and prepares me to go again. Recovery isn’t a luxury—it’s a weapon.

Mental Fortitude in Isolation

Mental resilience is just as critical as physical conditioning. Anyone who’s spent a night alone in a tent, soaked through, cold, with a failed fire and the wrong topo map knows that your mindset determines your outcome.

Define Mission Success. In the military and policing worlds, mission failure is not an option. Your reputation—and sometimes lives—depend on mission success. In the backcountry, you need to define what success looks like for you. For me, success is the ability to move into an area, locate animals, and make future assessments about trophy quality. That’s the mission.

Too often we let convenience win. We plan a long movement over rough terrain, but stop short because there’s a hut or a flat bit of ground that looks “good enough.” We convince ourselves the animals are nearby. That’s mission drift. Push past it.

Surround yourself with people who are like-minded in their commitment. I recently relocated to the South Island after years of commuting from the North to chase red stags. I made that mission a defining part of my lifestyle—even switching professional roles to accommodate it. In March 2025, I shot my first truly mature red stag. The hunt covered 72km of backcountry, and my mate (a mentor) and I had to modify our approach—using mountain bikes to manage the distance. I hadn’t ridden a bike since my teens, but that didn’t matter. Mission success was on the line.

Conclusion: Earned, Not Given

Backcountry hunting is not a test of strength. It’s a test of consistency, humility, and resolve. The men and women who do it well have learned—often the hard way—that you don’t rise to the occasion; you fall to the level of your preparation. If you prepare well—physically and mentally—the hills might just let you leave with a story, some meat, and a quiet sense of pride.

Amazing article. I myself have been humbled many times in the hills of Aotearoa. It’s a tough physical game but even tougher mental game.